1

Jan

Jan

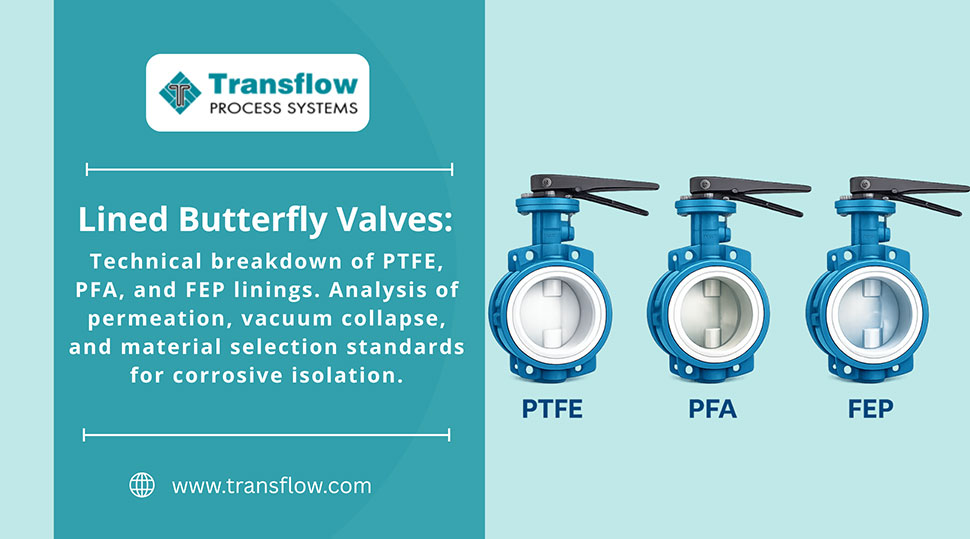

Lined Butterfly Valves: PTFE, PFA, and FEP in Corrosive Service

In chemical processing, the valve is usually the weak link.

Piping specs are rigorous. But valves? They often get value-engineered until

you’re left with a liner that can’t handle the reality of the line. The threat

isn't always a blowout. It’s the slow, quiet failure of the lining material.

Whether it's hydrochloric acid, brine, or chlorinated solvents, corrosive media

is patient. It finds the microscopic void. It breaches the barrier. Next thing

you know, the body corrodes, the valve seizes, and you’re shutting down the

unit.

Picking the right valve isn't just about checking a chemical resistance chart.

You have to match the physics of the liner—its density, its permeability, its

grip on the metal—to the actual stress of the process.

Reliability isn't accidental. It comes from an engineering culture that

prioritizes material science over simple cost reduction.

The Physics of the Liner: What You Are Actually Buying

PTFE, PFA, and FEP are all fluoropolymers. On paper, they look similar. In a

reactor or a transfer line, they behave differently. These materials form the

foundation of modern lined piping technology, and swapping one for the other

without thinking is a common root cause of failure.

1. PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene)

The industry workhorse.

- Why use it: Incredible chemical resistance and very low friction. It keeps torque low, which saves on actuation costs.

- The catch: It’s usually paste-extruded or isostatically molded. If the process isn’t tight, you get microporosity. For general slurry or acid, that’s fine. For high-permeation gas like Chlorine? It’s a risk.

2. PFA (Perfluoroalkoxy)

- Why use it: Because it flows, it can be injection molded. This creates a denser, less porous liner that anchors better to complex shapes like the disc and stem.

- Best for: High purity, high thermal cycling, or anywhere permeation is your nightmare scenario.

3. FEP (Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene)

- The fit: It gives you that melt-processable density without the PFA price tag. Good for standard chemical duties where you don't need the extreme temperature range.

Similar to PFA, but with a lower heat ceiling (usually maxing out around

150°C/300°F).

Why Specs Fail (The Stuff Datasheets Don’t Tell You)

You can pick the right material and still lose the valve. This becomes clear

when you examine the detailed construction of a robust lined butterfly valve,

which must be engineered to address mechanical realities that standard

datasheets often ignore.

The Permeation Problem In chlorine or HF service, permeation is a known killer.

Small molecules migrate right through the liner. They hit the metal interface,

get trapped, and form blisters. Eventually, the blister grows until it collapses

into the flow.

The Vacuum Trap Steam-in-place (SIP) cleaning is brutal on liners. You steam the

line, then it cools. Rapid cooling creates a vacuum. If that liner isn't

mechanically locked to the body—standard design guidance in ASME B31.3—the

vacuum sucks it right off the metal. In plants that run frequent SIP cycles,

liner collapse is frequently cited in failure analyses as a common contributor

to early valve failure.

Stress Cracking Thermal cycling expands and contracts the liner constantly. If

the crystallinity wasn't controlled during molding, the material is brittle. It

will crack at the stress points, usually near the seat.

Avoiding this starts with validation. Strict protocols, such as spark testing

and dimensional verification, are central to rigorous quality testing to ensure

every unit meets standards like ASTM F1545.

Vetting the Supply Chain

Don't look at the logo. Look at the build. The "cheapest" valve is often just

the one with the most expensive hidden costs.

A solid technical spec demands three things:

- Virgin Resins Only: No regrind. Re-processed material kills tensile strength and permeation resistance.

- 100% Spark Testing: Every single wetted surface needs to be spark tested. No spot checks. You need to find the pinholes before the acid does.

- Liner Thickness: Thin liners save the manufacturer money. They cost you reliability.

The Bottom Line

In corrosive environments, you pay for reliability one way or another. You either pay for the right PFA or PTFE liner upfront, or you pay for downtime later.

Move from "reactive replacement" to predictive safety. Account for the temperature, the vacuum, and the permeation risk.

For critical applications, consulting with an experienced application engineer helps validate liner selection against permeation and vacuum risks.